Until 1921 swarming locusts appeared to be different species. Their bodies and behaviour were completely different. However, in 1921 Sir Boris Uvarov completed significant studies showing that the locust was the same species under different population densities.

This research and discovery laid the foundation for the modern phase theory – now known as phase polyphenism (where a single genotype produces two or more distinct, discrete phenotypes in response to environmental cues, rather than continuous variation).

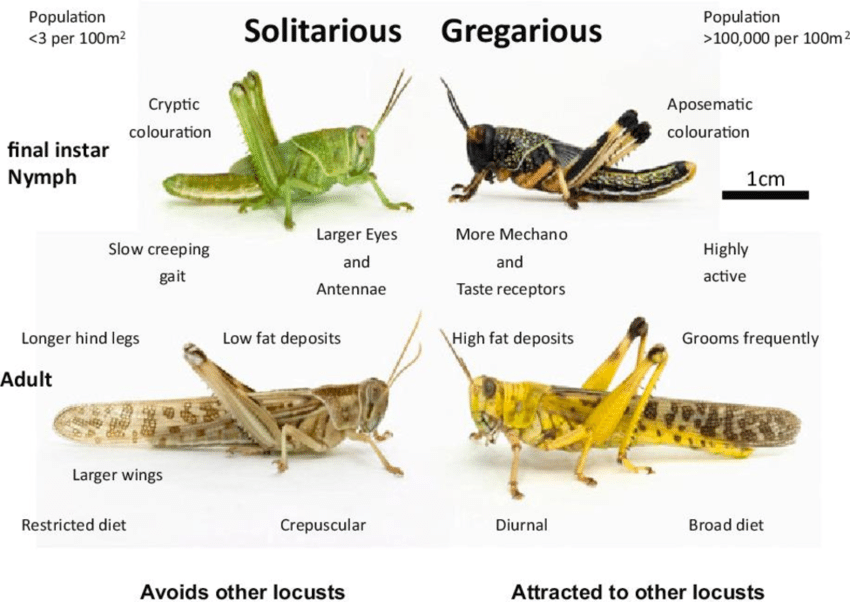

Phase theory tells us that some locust species exist in two different and reversible forms. The solitary form and the gregarious (sociable) form. These forms are driven by population density, environmental changes, and hormonal shifts.

The significance of this theory is that it explains why swarms appear and then disappear.

When environmental conditions such as rainfall following a drought the normally solitary insects are forced into close contact. The most potent trigger is the bumping of the hind legs which causes a rapid serotonin spike changing the behaviour within hours. Key pheromones recruit locusts in.

The serotonin spike overrides the normal aversion (fight or flight response) towards fellow locust peers. Higher levels of dopamine are also found linking with increased movement and reward seeking. It can mean being within the group is a pleasurable state. That said, the coherence of the group appears to be driven by cannibalism. Research has shown that gregarious (social) locusts are constantly trying to eat the locust in front of them for protein and salt, while simultaneously trying to avoid being eaten by the locust behind them. This “forced march” keeps the swarm moving in a unified direction. he neurochemical state is so powerful that it can be passed down. Gregarious mothers “prime” their eggs with chemicals that ensure the offspring are born with a predisposition toward the gregarious phase, even before they experience crowding themselves.

The swarm stops when the population density drops below a certain level eg through winds dispersing them, eating all the food including each other (starvation), fungi/parasites, and things such as winds blowing them into the ocean.

Low Population Density → Solitarious Phase (Schistocerca gregaria solitarious form)

│

│ Characteristics:

│ – Cryptic green/brown coloration for camouflage

│ – Avoids conspecifics (mutual repulsion)

│ – Low activity, sedentary lifestyle

│ – Restricted diet, low fat deposits

▼

Increased Population Density / Crowding

(Trigger: Tactile stimulation on hind femora + visual/olfactory cues from other locusts)

│

▼

Rapid Serotonin Surge (in thoracic ganglia)

(Within hours: 2–4 hours for behavioral shift)

│

▼

Behavioral Gregarization

- Increased locomotor activity

- Attraction to conspecifics (gregarious behavior)

- Reduced mutual repulsion

│

▼ (If crowding persists: days to generations)

Morphological & Physiological Changes - Darker/contrasting coloration (e.g., yellow-black patterns, aposematic in nymphs)

- Broader diet tolerance

- Higher fat deposits & energy reserves

- Frequent grooming

- Altered body proportions (e.g., larger overall size in adults)

│

▼

Gregarious Phase (Schistocerca gregaria gregarious form) - Forms dense marching bands (nymphs/hoppers)

- Adults form flying swarms

- Sustained forward movement driven by cannibalism risk (eat ahead / avoid being eaten from behind)

- Potential for large-scale plagues

│

└───────────────→ Density decreases / isolation

│

▼

Solitarization (reversible, often slower)

Back to Solitarious Phase

Several insect species exhibit phase transitions, most notably aphids (growing wings to flee overcrowding), armyworms (changing from green to black to march in groups), and Mormon crickets (forming massive walking swarms driven by nutrient cravings).